I AM TORN between two directions. I want to resume the survey of Lord Jesus Christ as soon as possible, as it simply covers so much important ground and is gathering fresh interest including a referral from Hurtado's blog himself. I also want to explore my deepening hunch that we need to be clearer that, like us, all of our predecessors in the Christian faith were also interpreters of that which preceded them. That is to say, in some clearer sense than before, we need to do away with the ideas that the "divinely inspired" writers of the New Testament were not interpreting according to principles that still govern us today. Same is true of Christian interpreters in the second, third and fourth centuries too. Obviously much more to be said about that. A key author in this field is Paul Ricœur, for whom I have received a specific request to relate his "arbitration" work to the question of the unfolding articulation of the centrality of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit in the first centuries (I also note that my article on hermeneutics received considerably more interest than average, see Hermeneutic Circle and asking better "why" questions).

Since it has always been the goal of this blog to not disenfranchise my French readers, and this second author is French (and I am reading him in French), I propose to do just a few posts (I'm aiming at three) in both languages on Ricœur and then pick things up again with Lord Jesus Christ.

The title I am referring to is The Conflict of Interpretations, which speaks directly to the sharply differing views to which I have been exposed over the last few years, and in many senses encapsulates the direction taken by the Triune Hub model I have been developing. English citations are my translations (which, since I am still grappling with Ricœur, may not be perfect, apologies). Page numbering is from the 2013 edition of Conflit des Interprétations: Essais d'Herméneutique, by Editions du Seuil, which is virtually unchanged from the original 1969 edition by the same publisher.

Our first citation seems to confirm this conviction that interpretation is integral not only to our acquisition of historical information but also the way in which that was originally composed itself in the past:

No striking interpretation can be drawn without borrowing from the modes of understanding available at a given time: myth, allegory, metaphor, analogy, etc. (p. 24)

Not only can we note that it that interpretative processes are constantly active, both now and the periods in the past that seems so vital to us, but that this leads us to a second observation: because this hermeneutic circle hugely exceeds the lifespan of any given interpreter, we should surely consider a real collective thought, comprehension and interpretation ascribable to the Church. This collective consideration may be close to Chad McIntosh's illustration of "Group Persons" in his exploration of new philosophical possibilities for a tri-personal God (see my 2015 article: "Jésus Sois Le Centre").

In surveying the early 20th century efforts to place Hermeneutics more centrally within the scope of human sciences, Ricœur covers Dilthey and his hermeneutic problem, which is profoundly psychological. This is because interpretation (e.g. of a text) is a small part of an individual's wider field of semantic reference, his "comprehension". To understand another person thus becomes seriously problematic and requires some form of conscious reception mechanism:

"To understand is to transport oneself into the life of another; historical comprehension brings into play the full force of historical inquiry: how can a historical being understand historically his history?... This is the major difficulty that can justify how phenomenological search for a reception mechanism, like grafting it onto a young plant" (p. 26).

"There are two ways to root hermeneutics phenomenologically, the short route and the long route. The short route is that of ontological comprehension"

"There are two ways to root hermeneutics phenomenologically, the short route and the long route. The short route is that of ontological comprehension"

The short route, to cut a long story short (!), is more problematic. It's like attempting historical surgery, and, most fascinatingly for our own interest in the Trinity, is obsessed by ontology. Guess what? That is precisely the form of expression (I choose these words carefully) that the victorious fourth-century bishops were so concerned adopting their understanding: identification of the Son with the Father and the Spirit, via... something ontological a.k.a. ousia. Here I need to be very careful not to mix up two independent critiques. We can criticise the fourth-century "Homoousians" (those who believed in the "consubstantiality" of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit) for inappropriate hermeneutic integration of their predecessors, or we can criticise later (e.g. 21st-century) historians for inappropriate hermeneutic integration - presuming some of the ontological categories to be valid while simultaneously stating that such categories cannot be applied to the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Assuming those ontological categories are biblical, you could perhaps continue to say the usage of those categories is downright "unbiblical", transgressing stacks of sound exegetical practice, and so on, while not seeking out what lay behind the form.

Ontological comprehension, says Ricœur, is an all-or-nothing affair, black and white. You've either got 1 God or three. You've either got a Unipersonal God or a Tripersonal God, etc.

The Long Route, on the other hand, will not devoid itself of ontology, but will access it via nuanced semantics, "by degree". That is a good term for my model of the Triune Hub: "semantics", which would seem to be situated within Ricœur's second category of hermeneutic. Why is that? I have a hard time explaining to some seasoned philosophers who reason in more black and white categories what I mean by this "hub". Semantic is a very good word to describe it. I also like "space" - I am referring to the Jewish mindset that, while not yet embracing a vocabulary of monotheism, had some strict semantic parameters in place about what could hitherto be said of Yahweh/[the] LORD via his agents and what could not. I like using the word "hitherto" very much; by it, I am of course referring to the events surrounding the life of Jesus, whose Jewish followers felt obligated to modify and reorganise their own monotheistic semantics and God's place within it.

La Voie Longue, en contre partie, n'abondonnera pas l'ontologie, mais l'accédera par la sémantique, "par degrés" (p. 27). Cela est un mot important pour mon modèle du Noyau Trinitaire: "la sémantique", ce qui correspondrait à la deuxième catégorie de Ricœur. Pourquoi? J'ai du mal des fois à essayer d'expliquer ce que j'entend par ce "noyau" à des philosophes bien rodés qui raisonnent avec des distinctions catégorielles bien plus noir et blanc. La sémantique est une bonne expression pour le décrire. J'aime aussi "l'espace" - je fais allusion à l'esprit Juif qui, même si pas encore doté d'un vocabulaire de "monothéisme", intégrait des paramètres sémantiques strictes de ce qui pouvait être dit des agents de Yahweh/L'Eternel et de ce qui nous pouvait pas être dit d'eux. Cependant, cela était jusqu'à l'arrivée de Christ qui a modifié cette sémantique et la place de Dieu dans cette organisation sémantique.

To inquire about the being of something in general [reference to ontology], we first need to inquire about the being that is the "that" of all being, that is to say, this being that exists in and through its mode of being understood.

This last quote is quite a lot of philosophical mumbo-jumbo and a difficult one to translate (for me), especially Ricœur's use of the preposition "sur" (typically simply "on", which I have rendered "in and through"). But if you get the contrast that Ricœur is driving his readers toward, especially when you are motivated by a key "conflict of interpretation" like I am in the case of fourth-century interpretations of the Trinity, we can maybe start to grasp the distinction in slightly less philosophical lingo. What I am saying is that Ricoeur is right in his drive to help us look at the mode of transmission of important theological information - we cannot strip it down naked so to speak. The bones always have flesh. But here is where we and the church can hit confusion because the very subject at hand is ontology (ousia, divine "substance" or "essence" linking the three Persons as one Godhead, then simply "God")! But we mustn't allow ourselves confusion between the packagin and the contents here, via this double usage of ontology. There is a "mode" at work of transmission of important theological information that has as much ontological importance as the ontology explicitly described.

More tomorrow! A suivre demain!

Since it has always been the goal of this blog to not disenfranchise my French readers, and this second author is French (and I am reading him in French), I propose to do just a few posts (I'm aiming at three) in both languages on Ricœur and then pick things up again with Lord Jesus Christ.

|

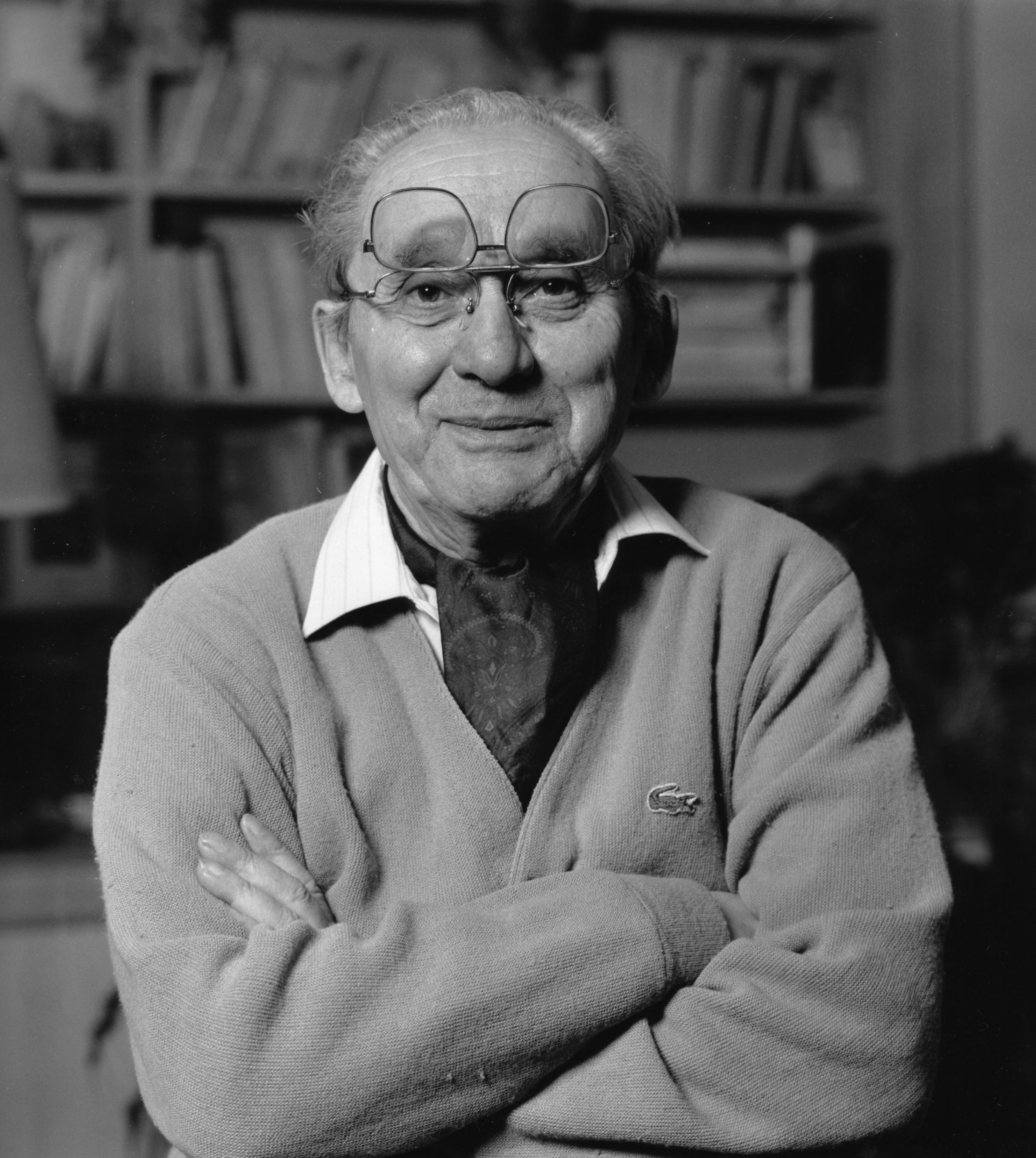

| Paul Ricœur |

Puisque ça a toujours été l'objectif de ce blog de ne pas perdre de vue mes lecteurs francophones, j'ai choisi de m'orienter maintenant pour quelques articles sur quelques citations de Paul Ricoeur avant de reprendre Lord Jesus Christ, par Larry Hurtado. En effet, j'ai reçu une demande de développer ce qui m'interpelle chez cet auteur français vis-à-vis de la Trinité, son rôle d'arbitrage étant important dans la question du déploiement de l'articulation de la place centrale dans la foi chrétienne qu'ont toujours occupé le Père, Fils et Saint Esprit dans l'esprit Chrétien.

The title I am referring to is The Conflict of Interpretations, which speaks directly to the sharply differing views to which I have been exposed over the last few years, and in many senses encapsulates the direction taken by the Triune Hub model I have been developing. English citations are my translations (which, since I am still grappling with Ricœur, may not be perfect, apologies). Page numbering is from the 2013 edition of Conflit des Interprétations: Essais d'Herméneutique, by Editions du Seuil, which is virtually unchanged from the original 1969 edition by the same publisher.

Our first citation seems to confirm this conviction that interpretation is integral not only to our acquisition of historical information but also the way in which that was originally composed itself in the past:

No striking interpretation can be drawn without borrowing from the modes of understanding available at a given time: myth, allegory, metaphor, analogy, etc. (p. 24)

Nulle interprétation marquante n'a pu se constituer sans faire des emprunts aux modes de compréhension disponibles à une époque donnée: mythe, allégorie, métaphore, analogie, etc. (p. 24)

Le titre auquel je fais allusion est Le Conflit des Interprétations, ce qui se situe pil là où il faut pour répondre aux perspectives fortement contradictoires auxquelles j'ai été confrontées ces dernières quelques années, et répond bien à l'orientation prise par le modèle du Noyau Trinitaire que je développe. Les citations sont tirées de l'édition 2013 de Conflit des Interprétations: Essais d'Herméneutique, par Editions du Seuil, ce qui reste pratiquement inchangé de l'édition 1969 par le même éditer. Cette première citation semble confirmer que l'intérpretation est intégrale non seulement à notre acquisition d'informations historiques mais aussi à comment ces dernières ont elles-mêmes été composées. Ce constat nous conduit à un deuxième: puisque le cercle herméneutique agit à travers des périodes de l'histoire qui dépassent la simple vie d'un tel ou tel interprète, nous pouvons constater qu'il existerait surement un niveau de réflexion, de compréhension et d'interprétation collective dont l'Eglise est le titulaire. Cette appropriation collective pourrait se rapprocher au sens voulu par Chad McIntosh dans ses illustrations de "personnes groupales" dans sa quête d'ouvrir de nouvelles possibilités philosophiques pour un Dieu multi-personnes (voir mon article de 2015: "Jésus Sois Le Centre").

Not only can we note that it that interpretative processes are constantly active, both now and the periods in the past that seems so vital to us, but that this leads us to a second observation: because this hermeneutic circle hugely exceeds the lifespan of any given interpreter, we should surely consider a real collective thought, comprehension and interpretation ascribable to the Church. This collective consideration may be close to Chad McIntosh's illustration of "Group Persons" in his exploration of new philosophical possibilities for a tri-personal God (see my 2015 article: "Jésus Sois Le Centre").

In surveying the early 20th century efforts to place Hermeneutics more centrally within the scope of human sciences, Ricœur covers Dilthey and his hermeneutic problem, which is profoundly psychological. This is because interpretation (e.g. of a text) is a small part of an individual's wider field of semantic reference, his "comprehension". To understand another person thus becomes seriously problematic and requires some form of conscious reception mechanism:

"To understand is to transport oneself into the life of another; historical comprehension brings into play the full force of historical inquiry: how can a historical being understand historically his history?... This is the major difficulty that can justify how phenomenological search for a reception mechanism, like grafting it onto a young plant" (p. 26).

Comprendre c'est... se transporter dans une autre vie; la compréhension historique met ainsi en jeu tous les paradoxes de l'historicité: comment un être historique peut-il comrendre historiquement son histoire? ... Telle est la difficulté majeur qui peut justifier que l'on cherche du côté de la phénoménologie la structure d'accueil, ou.... le jeune plant sur lequel on pourra enter le greffon herméneutique. (p. 26)

En reprenant les efforts du début de 20ème siècle pour placer l'herméneutique au centre des sciences humaines, Ricœur note le problème fondamental de l'herméneutique décrit par Dilthey. L'hermeneutique est profondément psychologique, puisque l'interprétation (d'un text notamment) est en effet une petite part d'une masse sémantique de référence plus large de la "compréhension". Comprendre donc l'autre devient sérieusement problématique et nécessite un méchanisme de réception qui joue sur le conscient (voir citation dessus de p. 26).

On est au point de voir la pertinence absolue de l'hermeneutique à la question de l'émergence du Dieu trinitaire à la fin du quatrième siècle et faire face aux choix que l'herméneutique pose devant nous.

And so we are just about ready to observe the absolute relevance of this study of hermeneutics to the question of the late fourth-century emergence of the Triune God and face the choices hermeneutics place before us.

"There are two ways to root hermeneutics phenomenologically, the short route and the long route. The short route is that of ontological comprehension"

"There are two ways to root hermeneutics phenomenologically, the short route and the long route. The short route is that of ontological comprehension"

Il y a deux manières de fonder l'herméneutique dans la phénoménologie...la voie courte et la voie longue. La voie courte c'est celle d'une ontologie de la compréhension (p. 26-27)

La voie courte, pour aller vite (!), est plus problématique. C'est un peu comme tenter une intervention historique chirurgicale et serait particulièrement concernée par l'ontologie, d'un intérêt tout particulier pour notre sujet de la Trinité. C'est tout à fait dans cette forme d'expression (je choisis mes mots avec prudence) que les évêques victorieux du quatrième siècle voulaient exprimer leur compréhension: l'identification du Fils avec le Père et l'Esprit, via... quelque chose de l'ordre ontologique, notamment "ousia".

La compréhension ontologique, dit Ricœur, c'est une approche tout-ou-rien, noir ou blanc. Soit vous avez un Dieu ou trois dieux. Soit vous avez un Dieu unipersonnel ou tripersonnel, etc.

The Long Route, on the other hand, will not devoid itself of ontology, but will access it via nuanced semantics, "by degree". That is a good term for my model of the Triune Hub: "semantics", which would seem to be situated within Ricœur's second category of hermeneutic. Why is that? I have a hard time explaining to some seasoned philosophers who reason in more black and white categories what I mean by this "hub". Semantic is a very good word to describe it. I also like "space" - I am referring to the Jewish mindset that, while not yet embracing a vocabulary of monotheism, had some strict semantic parameters in place about what could hitherto be said of Yahweh/[the] LORD via his agents and what could not. I like using the word "hitherto" very much; by it, I am of course referring to the events surrounding the life of Jesus, whose Jewish followers felt obligated to modify and reorganise their own monotheistic semantics and God's place within it.

|

| Image taken from https://www.centre4innovation.org/ |

La Voie Longue, en contre partie, n'abondonnera pas l'ontologie, mais l'accédera par la sémantique, "par degrés" (p. 27). Cela est un mot important pour mon modèle du Noyau Trinitaire: "la sémantique", ce qui correspondrait à la deuxième catégorie de Ricœur. Pourquoi? J'ai du mal des fois à essayer d'expliquer ce que j'entend par ce "noyau" à des philosophes bien rodés qui raisonnent avec des distinctions catégorielles bien plus noir et blanc. La sémantique est une bonne expression pour le décrire. J'aime aussi "l'espace" - je fais allusion à l'esprit Juif qui, même si pas encore doté d'un vocabulaire de "monothéisme", intégrait des paramètres sémantiques strictes de ce qui pouvait être dit des agents de Yahweh/L'Eternel et de ce qui nous pouvait pas être dit d'eux. Cependant, cela était jusqu'à l'arrivée de Christ qui a modifié cette sémantique et la place de Dieu dans cette organisation sémantique.

Pour s'interroger sur l'être en général [référence ontologique], il faut d'abord s'interroger sur cet être qui est le "là" de tout être..., c'est à dire sur cet être qui existe sur le mode de comprendre l'être. (p. 28, mon accentuation)

To inquire about the being of something in general [reference to ontology], we first need to inquire about the being that is the "that" of all being, that is to say, this being that exists in and through its mode of being understood.

This last quote is quite a lot of philosophical mumbo-jumbo and a difficult one to translate (for me), especially Ricœur's use of the preposition "sur" (typically simply "on", which I have rendered "in and through"). But if you get the contrast that Ricœur is driving his readers toward, especially when you are motivated by a key "conflict of interpretation" like I am in the case of fourth-century interpretations of the Trinity, we can maybe start to grasp the distinction in slightly less philosophical lingo. What I am saying is that Ricoeur is right in his drive to help us look at the mode of transmission of important theological information - we cannot strip it down naked so to speak. The bones always have flesh. But here is where we and the church can hit confusion because the very subject at hand is ontology (ousia, divine "substance" or "essence" linking the three Persons as one Godhead, then simply "God")! But we mustn't allow ourselves confusion between the packagin and the contents here, via this double usage of ontology. There is a "mode" at work of transmission of important theological information that has as much ontological importance as the ontology explicitly described.

Cette dernière citation contient pas mal d'expressions difficiles et la traduction en anglais pour moi n'était simple, surtout l'emploi de Ricœur de la préposition "sur". Mais si vous comprenez le contraste que Ricœur veut mettre en lumière, surtout lorsqu'on est motivé par "conflit d'interprétation" comme je le suis dans le cas des interprétations du quatrième siècle de la Trinité, peut-être que nous pouvons commencer à saisir la distinction par des termes moins philosophiques. Ce que je veux dire c'est que Ricoeur a raison lorsqu'il insiste à ce qu'on regarde le mode de la transmission d'informations théologiques importantes - on ne peut pas les réduire comme informations brutes. Les os sont toujours recouverts de la chaire. Mais c'est bien là où nous et l'Eglise pouvons nous heurter à la confusion puisque le sujet même c'est l'ontologie ("ousia", la substance divine qui relie les trois Personnes dans un seul Dieu)! Mais nous ne pouvons pas nous permettre à confondre ce contenu ontologique de son emballage ontologique. A l'oeuvre ici est et était un "mode" de transmission d'informations théologiques importantes aussi important que son contenu.

More tomorrow! A suivre demain!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks very much for your feedback, really appreciate the interaction.